|

Questions to the Artist Extract from : François Méchain / Regard d'artiste - Perspectives

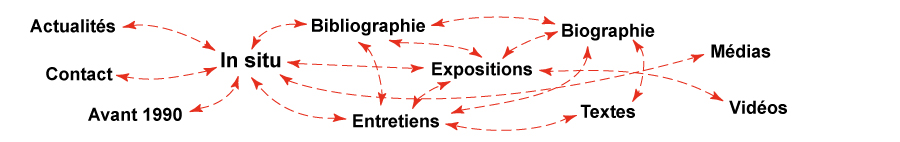

Colette GARRAUD : You have chosen to install your sculpture on that part of the Trvarez Estate known as the formal garden, i.e., the French-style parterre that is located between the vertugadin [amphitheatral sloped garden lawn] - separated by camellia shrubs - and the esplanade of the cour dŐhonneur, in front of the chteauŐs southern-facing facade. This formal garden was completely overgrown for a long time but was restored a few years ago. Can you describe your artistic project and the experience that awaits visitors? Franois MCHAIN : Above the vertugadin, in line with the symmetrical beds, visitors will immediately notice the large golden metal birdcage, whose impressive dimensions - the cage is three metres high - and open door are sure to incite visitors to enter the structure. The door will automatically close behind the visitor with a click. Although it will be easy to open and get out, the visitor will still feel a certain sense of unease. The origin of this idea lies in my memory of a visit to the Jewish Museum in Berlin, with its tall black Holocaust Tower. Here, the door closes in a similar fashion - albeit in a much more tragic context - slamming shut behind the person who has just entered the tower. C.G.: You have always respected the principle that any in situ creation should first and foremost be shaped by the type and history of the landscape in which it is presented and on a formal level, this entire project fits perfectly with the landscape and original architecture of the estate. The sloping garden was designed precisely to be admired from the windows of the chteau and ironically, your use of classical broderies - albeit in a rather unorthodox style - completes the restoration of the parterres. F.M.: I also plan to hang a large photographic triptych on the back wall, most certainly of the view of the parterre through the bars of the cage. This photograph will be positioned in such a way that it mirrors the view from the balcony. C.G.: We will, of course, go back to the social and political criticism which has with time become a central element of your work. But for the moment, I would like to focus on your artwork at Trvarez. Once again, you pair in situ sculpture and photography together. This pairing of media can be seen throughout your Ďuvre, regardless of the initial artistic intention or theme, but your Trvarez piece does this in a new way. Referring to some examples, even old ones, I would like if you could evoke the various forms that this dual approach has taken at the different sites where you have worked over the years. F.M.: Originally, I was a photographer (with a penchant for painting) and I have never abandoned these roots. Already in my first photographs, landscape, even a fictive one, played an important roleÉ C.G.: One thinks in particular of the quivalences Series(1982), whose title was a tribute to Alfred STIEGLITZŐs skies, especially the vertical sequence of six images, the first of which shows a snow-capped mountain which turns out to be, when one walks back from it, an image of a crumpled piece of paper on a table, which is itself situated in front of a snow-capped mountain. F.M.: Uncertainty is central to my work. In that sense, I am truly a descendant of MONTAIGNE. What interests me is the space between the object and its representation, the gap, the in-between and the uncertainty or doubts É the questions that this gap provokes. This gap can be found in the interface or interaction between in situ sculpture and the photograph of that same sculptural piece, which is in no way of a documentary nature, but is instead an autonomous photographic object. C.G.: Undoubtedly. However, working in situ - oftentimes in harsh landscapes such as an arid scrubland in Greece or the loneliness of large Canadian forests - is, at the same time, an experience that is far-removed from the work of the photographer in his studio. F.M.: I think a time came where being a photographer was no longer enough for me. I experienced the need to get my hands dirty as the saying goes. Working outside allows me to be truly at the heart of the landscape, confronted with certain challenges: the hunt or search for subject matter, the mastery of oneŐs materials, the passing time and weather. It is an exploration, a rediscovery of reality through oneŐs own physical capabilities. C.G.: In other words, an Exercice des choses* like the name you wanted to give to a monograph devoted to your work?(1) F.M.: Yes, because itŐs also about constructing forms in the landscape that evoke the landscape and which, even before the photographic action takes place, already contribute to a first distancing from reality. C.G.: Sculpture in situ is itself a kind of commentary on the essential role played by human history in a place. To my mind, the myth of a virgin nature is totally absent from your work. For an Ďuvre such as Kaissariani II (1993) for example, you installed on the slopes of Mount Hymettus, a pillar of scrubland plants supported on a mesh wire frame, ten metres in length, that lay amongst the cypress trees, reminiscent of an enormous ruin, while off on the horizon, one could make out the iconic white columns of the Parthenon. F.M.: This can only be seen in the photograph thanks to a little retouching. Otherwise, the Parthenon would have been shrouded in a thick haze caused mainly by pollution. C.G.: In this case, as in lots of your other works, the in situ sculpture cannot be viewed by the spectator. His only access to it is via the photograph. This was the same with La Rivire Noire [The Black River] (1990), which I believe to be one of the most significant pieces from this period. F.M.: La Rivire Noire is the name of an area in the Laurentides Forest Park. Here, I constructed an ephemeral sculpture made from branches, the shape of which mirrored the mountains seen in the distance, a sculpture that was lost in the forest and which, no-one, undoubtedly, saw. It was completely designed with photography in mind because only a single angle allows for the perfect homothety of the crest of the pile of branches with that of the mountain. However, I wanted to record this confrontation (which we discussed earlier) between the subject matter and the site on the image. I did this in the form of an encrypted inscription, a little like a barcode, which can be deciphered as follows: my height and arm span (100), length and maximum diameter of the birch trunks transported (BO 100 35), length and maximum diameter of the barberry trunks transported (EPI 350 10), duration of the action (8 hrs) and date (1990). Thus, inscribed on the epigraph and on the image, we have manŐs measurements in relation to the landscape. C.G.: However, the gap or margin between the image and reality appears emphasized rather than reduced, even if the spectator holds the key to its interpretation, which is generally not the case. The name of the place, also marked on the photo, on the other side of the diptych, is obviously more meaningful than the epigraph. F.M.: For me, a place name is a condensed version of its memory or history. Through it, I can recall an entire history of manŐs relationship with this place. In a world increasingly deprived of points of reference, I think that mankind cannot shape his present or his future if he doesnŐt have a good understanding or knowledge of what came before. C.G.: Here, as is often the case with Canadian toponymy, the place name surely represents the sense of fear or awe we experience when confronted with the immensity of the wilderness. F.M.: The interest in place names is also connected to my childhood as the son of a farmer. I used to look at the unusual-sounding or intriguing names on my fatherŐs land register like Ôcoute sŐil pleutŐ or ÔDne loupŐÉ And since weŐre on the topic of La Rivire Noire, I would like to add something. I received funding to live on site with the forest rangers and I was struck by the extent of the deforestation. The felled trees, like those I used in my sculpture, werenŐt being used for anything, as it would have been too expensive to transport them. Therefore, they lay rotting on the ground. It was at that very moment, I think, that I began to ask myself questions about certain ecological disasters. Indeed, for a time, the head of the forestry course at the Universit Laval in Qubec, had considered borrowing the diptych to use it as part of a national campaign against the destruction of forests (in the end this didnŐt come about). C.G.: I remember during a conference in Pau, for the exhibition Îuvres dŐarbres (2), you screened Richard DESJARDINSŐs film LŐErreur borale which paints a fairly terrifying picture of the destruction of Canadian forests. That said, if this issue was an underlying one, even if it were present at the genesis of the artwork, it doesnŐt really have a place in the end vision that the viewer has of La Rivire Noire, compared to numerous other artworks that you would produce later with a much clearer ecological message, such as this piece at Trvarez. For me, La Rivire Noire is above all a piece that speaks of the physical experience of the landscape on the one hand, and the medium of photography, on the other. To return to our earlier discussion on your dual approach and the variations in the interface between in situ installations and photography over the course of your career, I would like to cite another example: Double ngatif (1995). In this work, one finds these two aspects but the ephemeral sculpture remains visible on the lawn of the Chteau de Bailleul for an entire season. F.M.: The title was a humorous allusion to a major American land art work, Double negative, by Michael HEIZER. My work consisted of two strips of lawn which seemed to raise themselves off the ground and attach themselves onto a low branch of a plane tree (in reality, they were reinforced by wire meshing and were sown and watered all summer). The photographic diptych shows the work from two different points of view, a positive from one angle and a negative from the other. The printing of the negative was a complex process that required an additional impression. C.G.: With that piece, we have a real reflection on the medium of photography itself and on the way in which photography profoundly changes our vision of reality. F.M.: It is worth remembering that at the time I was working exclusively in black and white because I used to print my own very large-scale photographs. A fairly complex and physically demanding task. I often willingly referred to myself as a darkroom sculptor. C.G.: It seems to me, that like many others, you were concerned at that point with the renewed celebration of that truly miraculous moment when the image appears, as well as having a strong relationship to the roots of photography, conceived as an impression from a distance, the notion of the Pencil of nature, as Henry Fox TALBOT (3) once referred to it. The idea here was that through photography, nature was involved in its own representation. You have also openly quoted Ansel ADAMS who considered the negative a score and the photographic print a performance. You used negatives as promises in order to work on values ? and contrasts such as those of a photographic sculpture. F.M.: Moreover, it is probable that my late passage to colour photography and particularly digital photography, while distancing me from the emergence or birth of the image during the printing process, privileged the evolution of my work towards a more socio-politically committed standpoint. Whatever the case may be, the Double ngatif diptych shown at the Galerie Michle Chomette, was never on display at the same time, or in the same place, as the sculpture in the Parc de Bailleul. C.G.: Very different then to this mirror-image work you have created at TrvarezÉ F.M.: Indeed. But there have been lots of other works in this vein. For example, for Entre digue et murs, ou comment lŐhistoire balbutie (2010), the large wall that I erected in La Rochelle and the photograph of the installation were both visible in the town at the same time, albeit in separate venues. There again, as always or almost always, the history of the place generated the work É More specifically the memory of the horrendous siege of La Rochelle and the seawall that RICHELIEU had constructed in 1627 to protect the city. In the Parc dŐOrbigny, I constructed a wooden wall over twelve metres long which blocked the view of the sea. In the middle of the wall, a peephole, inspired by the ones typically found in prisons, allowed the public to see the buoy that today marks the spot of the forgotten seawall, of which a few stones, the only remaining relics, lie scattered nearby. C.G.: Although this work was anchored in a specific event from the past, it was also relevant in terms of todayŐs geopolitics. It is part of a series of pieces focused on the issue of borders and evokes the numerous walls that conflict, fear and hatred have erected throughout the world. F.M.: In a fortuitous coincidence, a group of activists supporting the Palestinian cause plastered their posters on the wall. The photograph, which was almost five metres wide, was displayed close by as part of a retrospective exhibition of my work, but the two pieces, as I already mentioned, were never displayed together. Perhaps one could even talk of a triangle effect in that the painting done by Henri-Paul MOTTE in the nineteenth century represents RICHELIEU at the Siege of La RochelleÉ C.G.: Éa picture that we used to see in history booksÉ F.M.: Éa painting which is still on display at the Muse dŐOrbigny. C.G.: As we have already mentioned on several occasions, the site really determines the form of your work. Moreover, you have declared being attached to poor sites, sites that have little to offer at first glance. I note, however, that amongst your prolific productions, there are numerous exceptions to this principle, including of course, your work at Trvarez. When you first arrived here, what were your impressions or feelings about this place and how did these affect the direction that your work took? F.M.: This chteau is an outrageous undertaking that gives the impression of a collage, between its dated neo-Gothic vision and its strikingly modern features and facilities. I live close to Rochefort and this chteau reminds me of Pierre LOTIŐs house in terms of its artificiality, its manufactured aspect, but also for the feeling of pride conveyed by this edifice, constructed by a man who used every possible means to realize or achieve his dream. And when I saw those French-style parterres, I just wanted to disturb themÉ C.G.: You had however, as is often the case, imagined other projects for this site. In particular, you had for a time considered making use of the huge meadow, almost a plain that runs below the other side of the chteau for a landscape work that would have been visible from the esplanade. Can you tell us about it? F.M.: I was surprised by the fact that the de KERJGU brothers, Louis and Franois (father of the person who built the chteau) who purchased the vast estate of Trvarez, were experienced agronomists, interested in developing a modern agriculture that would be of benefit to the region. They did this through the introduction of techniques that were at that time unknown in France. I thought of my father who was passionate about farming, always concerned with improving machines, techniques of crop rotation, anything and everything that would allow him to produce more, and which, because mainly of my artistic nature, I was unwilling to emulate. But I remained however, particularly sensitive to issues such as these. I think that given the poverty of peasants in the nineteenth century and the necessity to feed people after the Second World War, this policy of overproduction made sense but it is a policy that is today out-dated, even dangerous. The ravages of farming and in particular, intensive farming are well-known, especially in Brittany. I certainly donŐt have any lessons to give anyone, and I know to what extent farmers are themselves limited by the cynicism and vagaries of the market, but I wanted to bear witness to this state of affairs. This was the origin of the project that I toyed with for a while, which would have consisted in partially burying old disused farm machinery in the soil of the large meadow and painting the visible parts in black (as a kind of homage to Anne and Patrick POIRIER). C.G.: The meadow would have been transformed into a seascape and the machinery would have been like dark rocks in the sea or the remains of a vast shipwreck. It would however, have required a huge amount of machinery to fill the enormity of such a vast landscape. In the end, your final project can be said to expand your general theory on economic and financial globalization. And if the metaphor that you give it is much less aggressive than the original project, it seems to me to be more insidious and perversely effective. In this work you operate a myriad of shifts in direction. You make use of French formal broderies, painstaking and expensive vegetal compositions in which artifice triumphs over nature. You introduce the explicit triviality of money into the apparently innocent field of the decorative pattern or motif, in the same way that in the past, subversive, political, or erotic motifs were inserted into grotesques. You trap the visitor in an aviary through the bars of which he can contemplate the park and the chteau, and you then turn the tables. The viewer becomes the viewed, transformed into a vulgar bird in a cage under the gaze of others. Speaking of the cage, you are planning to place the colour photograph of the Trvarez sculpture between two old black and white photographs, hung on the side walls. One of these portrays the huts in the Parc de Bailleul (1994) the other shows the Chambre dŐcoute (2003-2004). These two works, which might seem, at first glance, unrelated to the Trvarez in situ piece, suggest a new cross-disciplinary trajectory in your work. Viewed from a thematic perspective, in this instance the trajectory could be summarized as follows: from the hut to the cage, including the shed, the bedroom, the beehive, the templeŃin short, all of these spaces that you have built, that are either open or closed, which the viewer may (or may not) enter, and from which he may (or may not) contemplate, as from an observatory, the spectacle that surrounds him. F.M.: The first huts, of modest size, that I made in Bailleul in 1994 were visible in the park. Located under the large trees, their appearance perfectly conveyed the spirit of the site.É Redolent of childrenŐs games, it would have been impossible for even the smallest child to enter them as they were filled with either grass, branches or beech trunks, material borrowed from the site. In the photograph, they occupy the central section of the triptych, a process which I often borrow from religious paintingÉ C.G.: Why so? F.M.: I have always been fascinated by church altarpieces, an olden day form of the comic strip. I also like the etymology of the word religion [religere in Latin or relier in the French meaning to bind or to connect]. I even made a piece where I partially unhinged the side panels from the wall in the spirit of such altarpiecesÉ The huts in the central section of this photo triptych suggest the genesis of some primitive village, while in the left and right panels the viewerŐs gaze is attracted by the play of light and shadow in the indeterminate undergrowth off in the distance. C.G.: CouldnŐt we say that the hut is practically the perfect symbol of the original union between man and nature? It is undoubtedly one of the reasons why it is a recurring motif in many artistsŐ work, who like you, have placed the idea of nature at the centre of their Ďuvre, such as Giuliano MAURI for example with his Casa dellŐuomo (1985). This theme runs through all of your work and is oftentimes associated with that of the nave, which can be perceived as a kind of cabin or hut in reverse. Even recently, in the park of the Abbaye de Jumiges, you provided a poetic interpretation of LŐInvention de la Normandie (2013), featuring two wicker long ships, each over eight metres in length, one of which was overturned. The Ďuvre recalled the account, in part purely legend, of the settling of the Vikings, who used the shell of their boats as the roof of their houses. Gilles TIBERGHIEN notes on this subject that the French expression cabaner un navire [which translates literally as to upturn a boat and interestingly contains the word cabane for hut] means to chock it up (4). F.M.: I have also sometimes located the hut, and more precisely the impenetrable one, like those at Bailleul, in urban areas. Invited to work in Berlin, I built a shed, inspired by those found at the bottom of gardens, in the street in front of the Maison de France. The epigraph 9.11 [9 November] was carved all over the timber walls, deep enough to make holes in them. This is due to the fact that this particular date recurs throughout German history and marks a number of significant events, including - I cannot recall everything - the abdication of the Kaiser and the proclamation of the Republic (1918), HitlerŐs attempted putsch (1923), the Nazi party annual party (from 1933 onwards), the Night of Broken Glass (1938), the attempted assassination of Hitler (1939) and the fall of the Berlin Wall (1989)... This play on the date provided me with the opportunity to bore a hole, literally and figuratively, into the history of the world as I like to do. Passersby who tried to look into the shed through the holes in the wall were immediately blinded by a sudden flash of light. C.G.: A simple yet ironic sanction of the voyeurŐs reflex. If one were to interpret the installation in a superficial and playful way, one could say that the flash refers to the violence of history, the irregularity of memory, and suspicion of the futureÉ F.M.: I should mention that the shed was vandalized. I donŐt know if this destructive act had anything to do with the aggressive nature of the flash, but itŐs not impossible. C.G.: Indeed, the size of the walls, which are approximately the same height as a man, leads us to this interest in the measurement of the body and what this implies in relationship to the artwork. As we have mentioned, it was not possible to enter the shed in Berlin. On the contrary, with La Chambre dŐcoute (2003-2004), placed on the wall opposite the Bailleul huts, the spectator is placed at the centre of the space. F.M.: This in situ work was, in fact, a classroom from the Lyce Pierre-Gilles GENNES [secondary school], devoid of its furniture, transformed by the students and wallpapered over with leaves. The subtitle that I like to give it is: Feuilles de platane, bouleau blanc et odeurs fortesÉ [Plane leaves, white birch and strong odoursÉ] emphasizes the olfactory dimension, which is essential in our relationship to nature and is all too often overlooked today. C.G.: This brings to mind Wolfgang LAIBŐs wax bedrooms, including the extraordinary Chambre des certitudes (2001) at the Roc del Maur, opposite Canigou Mountain, whose rocky walls were covered with a fragrant wax É One also thinks of Giuseppe PENONEŐs laurel leaf decorated walls (Respirare lŐombra, 1999). F.M.: That project was yet again a dual artwork, consisting of the installation at the tip of the island - a hut of hazel branches woven together in such a way as to be as transparent as a piece of lace - and the photograph of the installation, subsequently exhibited at La Vitrine, a gallery space belonging to the Maison Europenne de la Photographie, responsible for commissioning the work. Sitting on the bench in the hut, with the ground covered in humus (again the olfactory dimension), the visitor could contemplate the other bank of the river Seine, one of the worldŐs most visited urban areas. In this space, visitors could dwell on a childhood memory or perhaps reflect upon the contradiction or paradox between the modern city, filled with the architecture of times past, and the primitive hut. At the time, I was interested in the Magdalenian site of Pincevent, in the ële-de-France region, discovered by Andr LEROI-GOURHAN. I was also interested in the origins of Lutetia. C.G.: The Vert-Galant hut, which is thus an observatory, is, in my opinion, inscribed in a corpus of contemporary works, which I have had the opportunity to christen, if I can quote myself, lieux pour le corps, machines voir (5) [places for the body, machines for seeing]. These are artworks, which may all look very different in appearance, but which fulfil three functions: visible in situ sculptures, shelters, observatories. These may be caves, cabins or huts, deliberately rudimentary, such as Chris DURYŐs Wave Chamber or Cloud Chamber, built from dry stones, logs, or reeds, huddled or rather half-buried in the landscape and fitted with a camera obscura, rendering a partial, intermittent, and fragile image of the surrounding landscape. These works may be found in the middle of nature or in a more ÔdomesticatedŐ environment with a park or a pavilion, from where one watches and sometimes from where one watches oneself watching, through the clever use of perspective or a game of mirrors. We can cite Sarkis at the Parc de Pourtals in Strasbourg, Daniel BUREN at the Fattoria di Celle in Tuscany, Perejaume at ErasmusŐ House in Brussels, James TURRELLŐs Skyspaces, Dan GRAHAM in the parks of the Muse KR LLER-MLLER in Otterlo or LofotenÉ to name just a few examples. But none of these artists add a photographic stage to their work. F.M.: With the Vert-Galant piece, the photograph consisted of a giant polyptych of 3.5 metres, reminiscent of those cardboard toys for children that have to be cut up, assembled and built. Each of these panels offered, through the mesh of branches, a view of the island, of the Seine and the aristocratic buildings on the other bank of the river. C.G.: It is, therefore, not insignificant that you called this photograph Le Balcon de lŐhistoire [The Balcony of History]. F.M.: It is another example of a piece that emphasizes the basics of shooting, point of view, focus, and framing. A few years prior to that, I had taken lots of photographs on an island offshore from Toronto, through a mesh of twigs constructed on the water (From Toronto to Toronto, 1996). Thanks to this frail vegetal curtain, I was able to make the buildings, head offices, and other symbols of the cityŐs economic power disappear at will. C.G.: Amongst these places for the body, machines for seeing that punctuate your work, we could also refer to Prcaires territoires (2012), a work dedicated to all the wild animals of the world that ridicules the concept of borders. This work features two matching huts, at a distance of twenty kilometres apart, on either side of the French-Italian border. The huts, in the shape of a beehive, are inspired by those seen at the Muse de lŐApiculture in Molines-en-Queyras and are arranged in an identical fashion. Only the landscape, which the visitor may observe through the opening of the huts, changes from one construction to the other. We can also refer to La Valle del Tempio (2008) in Sicily, an aerial construction in eucalyptus wood reminiscent of the famous dome of Monreale and a classical temple nearby. Tempio means temple in Italian and is also the name of the river which passes through the valley (again we find this recurring interest in words and polysemy. F.M.: The theme of the temple is a recurrent one in my work. I am currently developing a project for the town of Aubiet which consists of a circular space constructed around an oculus, on the model of the Roman Pantheon. The external wall, made of mirrors, will reflect the landscape, not very picturesque for that matter, while the interior wall will be covered with a panorama of family photographs donated by local residents. A temple of profane life, so to speak. C.G.: At Trvarez, what will the mirroring effect bring to the sculpture and its photograph? IsnŐt there a risk of repetition here? F.M.: I donŐt think so. What comes into play here lies in the order of interrogation, doubt, and ultimately verification. The photograph accentuates and reiterates the visibility, inscribing it within the strata of perception. The distance, although it may be reduced, will always be there, if only through the variations in the light, the weather, and the sculptureŐs evolution over time. Of course, the installation will only stay in place for the duration of the exhibition, but that aside, the garden of currencies is still ephemeral and will itself disappear once the flowers have withered and died. C.G.: The practice of ephemeral productions, as one knows, is common amongst artists who situate their work in the landscape, in part because it reflects the cycles of nature of which these Ďuvres are a part, but also because their ephemeral dimension ensures the preservation of the natural sites in which they are presented. There is already quite a long history of this. Richard LONG, Nils UDO, Andy GOLDSWORTHY, and so many others, have willingly worked with perishable materials, sometimes even snow and ice, in their concern not to leave a long-lasting trace on the landscape. Photography therefore appears as the indispensable corollary of this work of ephemeral nature. We are familiar with this quotation by Hamish FULTON : Take only photographs, leave only footprints. But we also know that this same individual declared : I am not a photographer (6) thereby signifying his desire neither to be associated with the idealization of the photographic image nor to question the properties of the medium. Used in this way, the photograph conforms with Roland BARTHESŐ words: A photograph is always invisible, it is not it that we see.(7) Obviously, your work reveals a totally different perspective. However, hasnŐt your transition to digital and colour photography changed the place that photography occupies in your creative process? HasnŐt it been relegated, in a way, to second place? C.G.: The theme of the tree could have been another leitmotif of your work. Again at Chaumont, you presented LŐArbre aux couteaux (2009), a tree made spiky with dozens of blades sticking out of its bark. F.M.: I donŐt always use trees in such a dark fashion. LŐArbre aux chelles (2009 - also in the same place - is proof of this, along with a more recent piece I created in the park of the Chteau de la Celle-Saint-Cloud, a site belonging to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I wanted to create an artwork in memory of the Marquise de Pompadour who had once lived there and FRAGONARDŐs painting Hasards heureux de lŐescarpolette [TranslatorŐs note: an escarpolette is a swing]. From a large Virginia tulip tree - the last living species in the Paris area - I hung twelve variations on the theme of a totally dysfunctional swing. There were swings where the seat was buried in a hole or occupied by a window box, where the seat took the form of a nail-studded fakir plank or double-seated confidantes-style swings... There was also a swing attached to two branches, swings that were too close together, as well as the perpetual swing equipped with a sound engine, measuring human time.. C.G.: In contrast to this poetic and playful work, the sculptures you have installed at Trvarez belong to that part of your work which could be characterized as activist artÉ F.M.: I donŐt really like that word. It has too many connotations.É Strictly speaking, I donŐt really position my work from a political standpoint. If I were to be considered an activist, it should be in the old sense of the word, i.e., the management of the city, the act of being a citizen of the world. It seems to me that an artist is obliged to provide a vision of his time. The language of art is, in any case, the only one I possess. Thanks to this language, I may perhaps generate or provoke something in another personŐs way of seeing the world. On this subject, Jochen GERZŐs work is exemplary. As for the change in my priorities over the course of the years, on that subject I would willingly quote BRAQUEŐs words, according to which, and I quote from memory, one recognizes the work of an artist by the quality of his transitions. C.G.: To illustrate the activist dimension that your work has taken, one could provide many examples. At Fontenay-le-Comte in the Vende, you hung childrenŐs clothes donated by local residents onto washing lines made of barbed wire, an installation that reminds me of a piece by Christian BOLTANSKIÉ F.M.: For whom I have great admiration. But it seems to me that BOLTANSKIŐs work is above all about memory and speaks of the past. For my part, I would like to play a role as a kind of whistleblower (a challenger of certitudes is the expression I once used) and what I am talking about is the futureÉ We should be concerned about the future we are passing down to our children, in the way that we hand down clothes to the generation that comes after usÉ C.G.: At this same site, you constructed a dilapidated crumbling wall with the word Democracy written on it É you filled an empty cellar with the deafening sound of tills and trolleys. Amongst the projects you didnŐt produce, you thought of putting the word Catastrophe in giant letters - inspired by the Hollywood sign - on the esplanade of the Domaine de Chaumont overlooking the Loire and even in the Parc de Versailles. You also planned a strange celebration of this mythical place that is Sainte-Victoire, with an assemblage of waste material collected on the road, whose shape, like La Rivire Noire sculpture, drew a visual rhyme with the peak of the mountain. Earlier we mentioned ... Durban ... and LŐArbre aux couteaux, which reveal this ecological concern that you have expressed so often. Is this also the underlying theme to the other piece that you installed today at Trvarez, the large metal sphere? F.M.: This sculpture is situated on the esplanade of the chteau, overlooking the immense space that stretches in front of the building. Visitors will most likely discover it upon leaving the garden, on their way back, and in a way, it is connected with the meaning of the cage and the broderies. I had a metalworker produce a globe of 3.5 metres in diameter, in blue-black steel. Visitors will be able to see through it (only the meridians and lines of latitude are indicated). The sculpture will eventually be torched following the exhibition... C.G.: One could make a comparison with the sphere of sculpted stone that occupies the centre of the formal garden, which was once part of a sundial. F.M.: As far as IŐm concerned, I introduce reality into this symbolic form, by inserting materials from the actual site into the sphere. These materials are either rhododendron branches, which along with the camellias, are one of the parkŐs richesÉ C.G.: On a similar note, last year Bob VERSCHUREN used the malleable branches of the rhododendrons for his Ďuvre installed in the stables of the estate. F.M.: By depositing vegetal matter found on the estate into the sphere, I am, in a way, writing the history of this site in the history of the world. A world, which it may be added, is somewhat batteredÉ

*The title of this monograph translates literally as the exercise of things. Here the word exercise may be understood in its original meaning from the Latin exercitium, i.e., physical or spiritual exercise, practice for the sake of training.

|